Ridesourcing apps like Uber, Grab, and DiDi have become ubiquitous in cities around the world but have also attracted much backlash from established taxi companies. Despite its adoption worldwide, regulation of ridesourcing services still varies greatly in different parts of the world - as policy makers struggle to assess its impact on the economy and society, with limited information and yet unidentified risks involved. One major consideration to improve mobility and sustainability in cities is whether ridesourcing apps serve as a substitute or complement for public transits. In an ideal situation, ridesourcing could complement transit service and help to reduce private car usage. However, as an alternative travel mode, it may also substitute for the transit.

To understand more about this and the impact upon cities, Hui Kong, Xiaohu Zhang, Jinhua Zhao from SMART Future Urban Mobility IRG and MIT JTL Urban Mobility Lab recently conducted a study that investigates the relationship between ridesourcing and public transit using ridesourcing data. Their findings were published in a research paper “How does Ridesourcing Substitute for Public Transit? A geospatial perspective in Chengdu, China” in the Journal of Transport Geography, and with a visualization of the study available here. Future Urban Mobility (FM) is an interdisciplinary research group (IRG) of Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), MIT’s research enterprise in Singapore.

Complement or Substitute

In the first such study undertaken by any researcher around the world to look into the substitution effect of each individual trip at the disaggregated level, SMART researchers used DiDi data in Chengdu, China, a major urban centre with a population of over 16 million people. They developed a three-level structure to recognize the potential substitution or complementary relationship between ridesourcing and public transit, while also investigating the impacts through exploratory spatiotemporal data analysis, and examining the factors influencing the degree of substitution via linear, spatial autoregressive, and zero-inflated beta regression models.

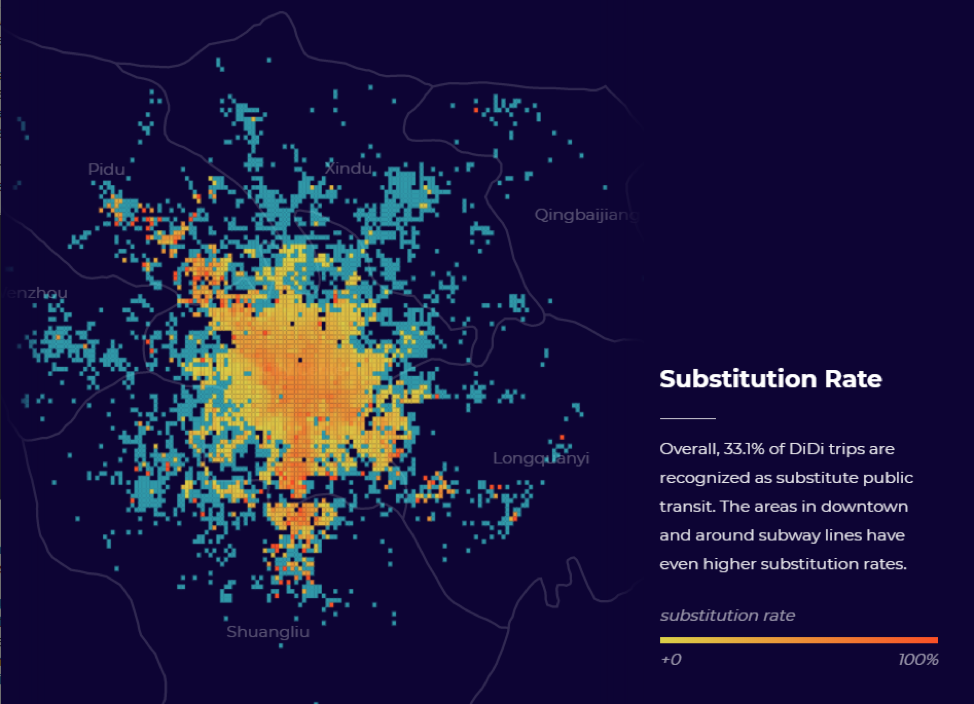

Through this, the researchers found that one third of DiDi trips potentially substitute for public transit, with a ridesourcing trip considered potentially a substitute for public transit if the trip can be effectively served by public transit.

The time of the day and the location does matter as well. The researchers found that the substitution rate is higher during the daytime (8am to 6pm) and more significant in the city center. Also, substitution trips appear more in the areas with higher building density and land use mixture. During the day, around 40% of DiDi trips have the potential to substitute for public transit, but the researchers found that this substitution rate decreases as the supply of transit decreases.

The researchers also found that the substitution effect is also more significant in the city centre and in more developed areas covered by subway lines, while peripheral and suburban areas were dominated by complementary trips. However they also note that house prices were positively correlated with the substitution rate, highlighting the importance of public transit to ensure less wealthy populations are served.

“High substitution rate implies the necessity of implementing ridesourcing regulations (e.g. spatial quotas, strategic pricing) or optimizing public transit service (e.g. shorten travel time, lower fee, improve crowdedness) in that area,” said Dr Hui KONG, SMART FM Investigator and Postdoctoral Associate at JTL Urban Mobility Lab and MIT Transit Lab. “The lower substitution in suburban areas can highlight areas where the current public transit service is inadequate and would help regulators decide on where to implement new bus or train lines.”

This research shows that ridesharing substitutes a large proportion of public transit. Therefore, it also amplifies the issue of digital divide. Afterall, most of the ridesourcing services rely on smartphone apps and credit card fare-paying. As a result, the unbanked population and the population that do not own a smartphone may not have access to ridesourcing services. Policymakers may have to rethink digitalisation efforts.